Force

A force can be thought of as a push or a pull

A force that acts by being directly in contact with an object is known as a contact force

- Friction and drag are both contact forces

A force that acts on an object at a distance is called a non-contact force or a force mediated by a field

The unit of force is the Newton (N)

- 1 Newton is the force exerted when holding 100g mass against the downward pull of gravity

If more than one force is acting on an object, the vector sum is known as the net force

- $\vec{F}_{\text{net}} = \vec{F}_1 + \vec{F}_2 + … \vec{F}_n$

The net force for a stationary object, or one that is moving at a constant velocity, is $0$, also known as equilibrium

The net force for an object that is speeding up, slowing down or changing direction is $\neq 0$

Newton’s Laws of Motion

First Law

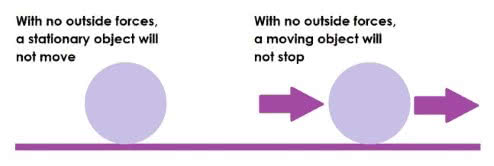

Every object will maintain a constant velocity unless an unbalanced external force acts on it.

Newton’s first law means that if an object has no forces acting on it, then it will continue to travel at its current speed and direction until an unbalanced net force acts on it

Newton’s first law is closely related to the concept of Inertia, the tendency of an object to resist any changes in motion

This resistance is related to the mass of the object, with more massive objects having a greater inertia

- The result of this is that to cause the same amount of change in motion, the amount of force increases proportionally to the amount of mass. This relationship is Newton’s second law

Second Law

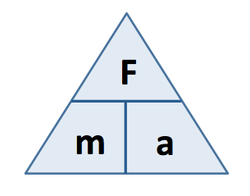

$\vec{F}=m \vec{a}$

$\vec{F}=\text{Force (Newtons)}$

$m=\text{Mass (kilograms)}$

$\vec{a}=\text{Acceleration }(m/s^2)$

- The acceleration of an object is directly proportional to the net force on the object, and inversely proportional to the mass of the object. Therefore:

- $1N = 1kg \times m/s^2$

- As a result, more force on the same mass means a greater acceleration, and an equal force on less mass also means a greater acceleration

- Newton’s Laws of Motions are all subject to vector addition and subtraction

Third Law

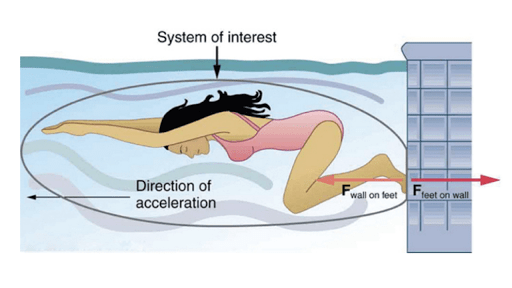

For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction

$\vec{F}_\text{AB}=-\vec{F}_{\text{BA}}$

If object A pushes on object B with $x$ Newtons of force, object B will push back on object A with $x$ Newtons of force

$\vec{F}_\text{AB}$ and $\vec{F}_{\text{BA}}$ are known as an action-reaction pair

Newton’s third law only applies to forces acting on different objects

| Action Vector | Reaction Vector |

|---|---|

$F_\text{by foot on ball}$ | $F_\text{by ball on foot}$ |

$F_\text{by car on bus}$ | $F_\text{by bus on car}$ |

$F_\text{by brick on Earth}$ | $F_\text{by Earth on brick}$ |

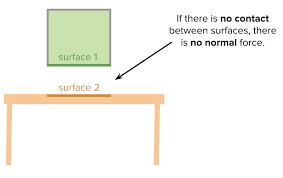

The Normal Force

When a smaller object (object A) falls under the influence of a force (such as gravity) from a larger object (the Earth), the effective force on object A is easy to observe

The action force is the gravitational force of the Earth being exerted on object A

In this case, ignoring air resistance, object A will accelerate downward at $9.8m/s^2$

If object A is then placed at rest on the floor, the gravitational force $\vec{F}=m\vec{g}$ is still acting on it, but it is at rest

According to Newton’s first law, an object can only be at rest if all the forces acting on it are balanced, so there must be a force counteracting gravity

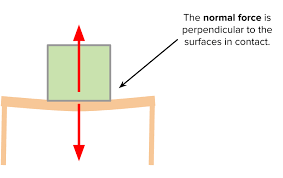

This is known as the normal force $(\vec{F}_N)$

The normal force acts with the same magnitude as its reactant force, but perpendicular TO THE SURFACE THE OBJECT IS ON (this will be an important distinction later)

It is important to note that the normal force and the reaction force from the third law are NOT THE SAME!!!

- This is because the normal force and its opposite act on the same object, while Newton’s third law acts on two different objects

Weight and the normal force do not make up an action-reaction pair, because they both act on the same object

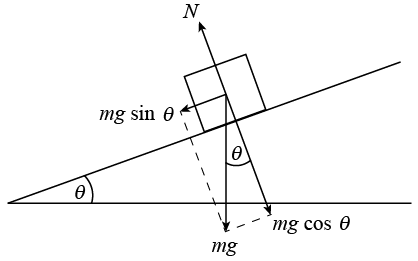

The Inclined Plane

In previous examples of the normal force, the surface has been horizontal. However, an object can be placed on a surface that is tilted at angle $\theta$ to the horizontal

Even on a tilted surface, $\vec{F}=m\vec{g}$ still acts downwards

However, the normal force acts at right angles to the SURFACE, and will change in magnitude according to the following formula:

$\vec{F}_N=m\vec{g}\cdot cos\theta$

THe motion of the object will then be affected by friction, if it is present

The component of the weight force that acts ALONG THE SURFACE is given by

$\vec{F}=m\vec{g}\cdot sin\theta$

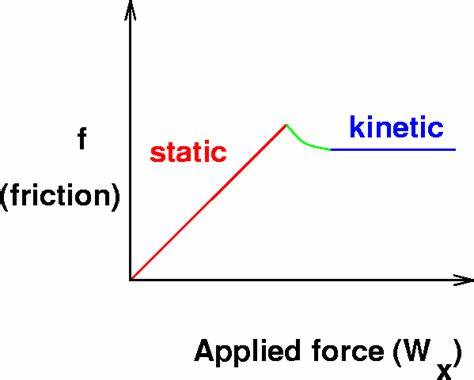

Friction

- Friction is expressed as $F=\mu F_N$, where $\mu$ is the Coefficient of Friction

- Note that Friction is directly proportional to the Normal Force, meaning that the frictional force at an angle is different to the frictional force on a flat plane

Energy

Energy is defined as the capacity to cause change

- For example, a moving car has the capacity to cause change if it collides with something else

Energy is SCALAR (no direction) and is measured in $\text{Joules }(J)$

- 1 Joule is the amount of energy required to lift a 1kg mass to a height of 0.1m (10cm)

- Joules are also sometimes expressed as $Nm,$ or Newton-Meters. The reason for this is explained here.

- There are 2 main categories of energy: kinetic and potential

- Kinetic energy is primarily associated with motion, but also includes less visible forms of energy, such as heat and sound

- Potential energy is the energy of an object based on its position in a field

- Examples of potential energy include gravitational, magnetic, and elastic potential energy

Work

When a force acts on an object and causes energy to be transferred or transformed, physics refers to this as “work”

Work is a change in energy $(W=\Delta E)$

DEFINITION: Work is the product of the net force causing the energy change and the displacement of the object in the direction of the force during the energy change. 1

Quantifying Work

Since work is a change in energy, the unit of work is also Joules $(J)$

The formula for work is:

$\color{lightblue}{W=\vec{F}_{net}\vec{s}}$

$W: \text{Work }(J)$

$\vec{F}_{net}:\text{Net Force }(N)$

$\vec{s}: \text{Displacement }(m)$

Since $W=\vec{F}_{net}\vec{s}, 1J=1N\cdot 1m=1Nm$

Therefore, 1 joule is 1 newton metre

- In other words, a force of 1N, acting over a distance of 1m, does 1J of work

Using the definition of a Newton, work can be defined in Base SI units:

- $1J=1N\times 1m = 1kgms^{-2}\times 1m =1kgm^2 s^{-2}$

Note that work is scalar, even though it is composed of 2 vectors

Work and Friction

- In an ideal situation where there is no friction, 100% of work is transformed into kinetic energy

- However, in most real situations, some of the work done on an object is converted into heat and sound

- In a situation where the net friction force and net work force are balanced, Newton’s first law dictates that the object will maintain a constant velocity

Force without Work

According to the definition of work, an object must move to say that work has been done

Therefore, if a force is applied to an object but the object does not move, then no work has been done

This can be proven mathematically:

$W=\vec{F}_{net}\vec{s}$

$\text{Substitute }\vec{s}=0$

$W=\vec{F}_{net}\cdot 0$

$=0,\text{ }\therefore\text{No work has been done.}$

Work and Displacement at an Angle

- When a force is applied, sometimes the object does not move in the same direction of the force

- In this case, the component of the applied force that acts on the object is considered the net force

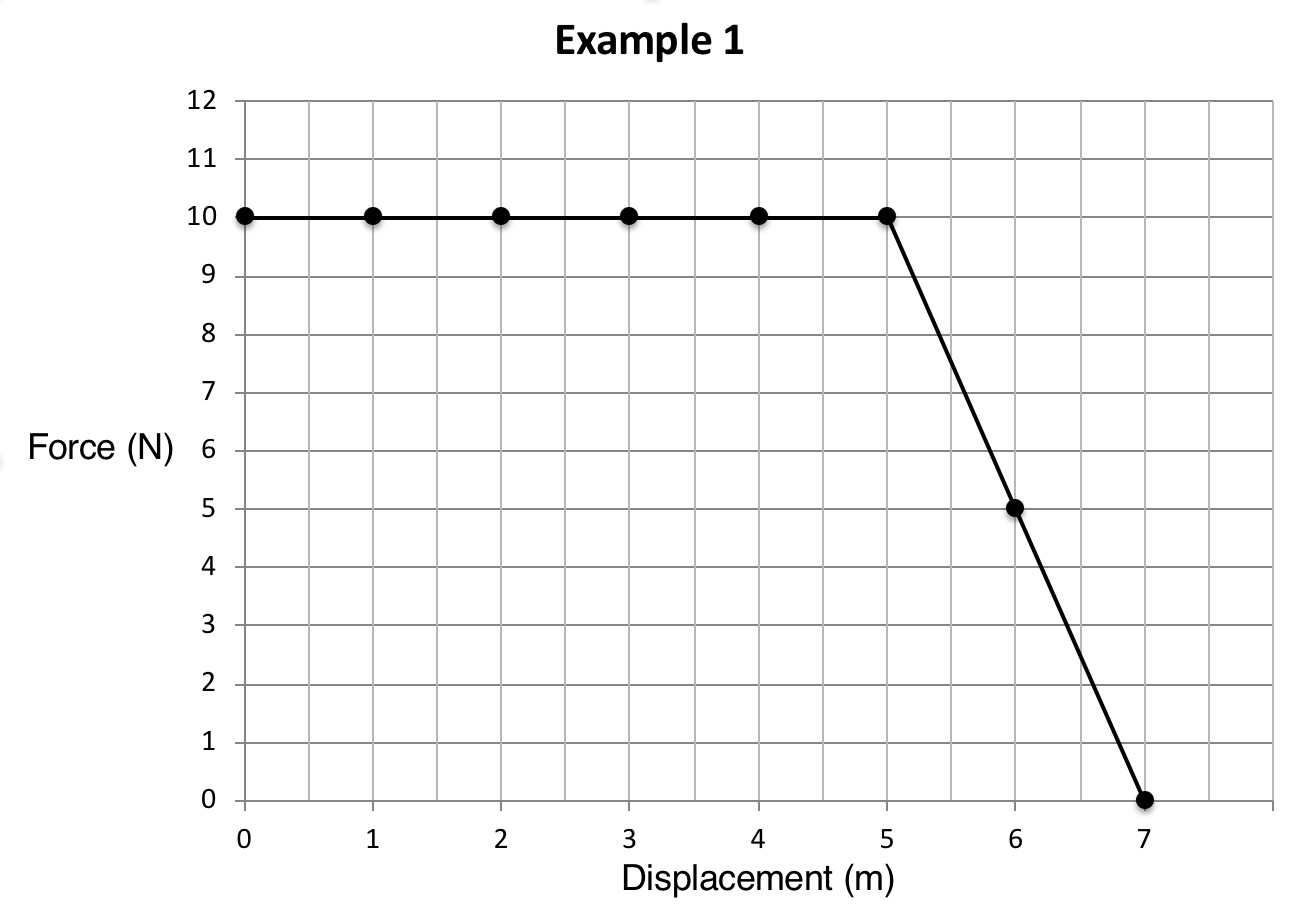

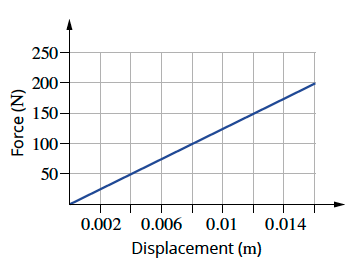

Force-Displacement Graphs

- Force-Displacement graphs illustrate how a force changes with displacement 2

- When a force changes with displacement, the net amount of work done can be calculated by finding the area under the Force-Displacement graph

- If the graph is a flat, horizontal line, then a constant amount of force is being applied

- The force displacement graph for pulling a spring, for example has a gradient >1, because there is a greater force required the more you stretch it

Conversion and Transformation of Energy

Moving objects, by definition, have kinetic energy, which can be quantified using mathematics.

Work-Energy Theorem

$W=\frac{1}{2}m\vec{v}^2 -\frac{1}{2}m\vec{u}^2$

The work energy theorem can be used as a definition for change in kinetic energy:

$W=K*{final}-K*{initial} =\Delta K$

Kinetic Energy Formula

$E_{k}=\frac{1}{2}m\vec{v}^2$

Gravitational Potential Energy

Note: I’m probably going to just shorten “Gravitational Potential Energy” to “GPE” in this section, just because I can. If you don’t like it, feel free to use the edit link to “fix it” - Jackson Taylor

Any object that is influenced by a gravitational field possesses gravitational energy

GPE can be defined as:

DEFINITION: The amount of energy available to an object as a result of its position in a gravitational field.

Work done against gravity can be expressed as

$W=\vec{F}_{net}\vec{s}=\vec{F}_g\Delta\vec{h}$

Because $F=m\vec{g},$ we can say that

$W_{gravity}=m\vec{g}\Delta\vec{h}$

Gravity is represented in equations by $\Delta U$ for some reason, so the final equation is

$\Delta U=m\vec{g}\Delta\vec{h}$

GPE is a form of energy, and is therefore SCALAR. This means direction doesn’t actually matter in the equations, even though most of the equation is made of vectors.

Elastic Potential Energy

Elastic potential energy is found in elastics (duh), springs, basically anything that can be stretched or squeezed

The elastic potential energy $(U_E )$ of an object is given by:

$U_{E}=\frac{1}{2}kx^2 $

$k:\text{The spring constant of the material}$

$x:\text{The amount of extension/compression of the object}$

Mechanical Energy and Power

Mechanical energy is the energy that a body possesses because of its position or motion

Mechanical energy is based on the Law of Conservation of Energy:

Law of Conservation of Energy: The total energy of an isolated system remains constant over any period of time without external influence.

Because of this, mechanical energy can be defined as “the sum of ALL kinetic and potential energies attributed to an object.”

This can be expressed mathematically as:

$E_m =K+U=\frac{1}{2}m\vec{v}^2 +m\vec{g} \vec{h}+\frac{1}{2}kx^2$

Most of the time, the $\frac{1}{2}kx^2$ part of the Mechanical Energy equation (elastic potential energy) is ignored.

The mechanical energy formula is useful for converting between kinetic and potential energies

- For example, consider a ball of mass 60g, which falls from a height of 1m.

- Initially, the ball has a kinetic energy of 0J, and a gravitational potential of $ 0.06\times 9.8\times 1=0.588J$

References

Dommel, A., Dommel, N., Hamilton, M., Hebden, K., Madden, D., & Stanger, J. (2017). Pearson Physics 11 New South Wales Student Book (1st ed., p. 157). Pearson Australia. ↩︎

ScienceFlip. (n.d.). Force-Displacement Graphs – Learn – ScienceFlip. ScienceFlip – A Resource for Students and Educators. Retrieved July 10, 2020, from https://www.scienceflip.com.au/subjects/physics/dynamics/learn12/ ↩︎